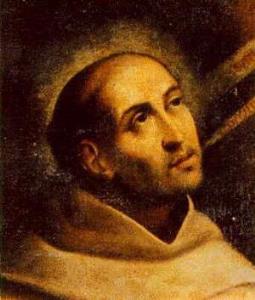

St. John of the Cross, author of the Dark Night of the Soul

Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God (Matthew 5:8).

Over five centuries ago, the Spanish Carmelite monk, St. John of the Cross, got fed up. Too often his fellow spiritual directors misunderstood the concerns of the monks and pilgrims in their care, failing to clarify and verify God’s work in their souls.

Specifically, some presented concerns over lost sweetness and joy in their usual spiritual exercises. Consolations of divine presence seemed distant but persistent memories. They kept coming to the table for the bread and wine, but the bread seemed stale, the wine flat, and the ritual monotonous.

Errant directors diagnosed them with melancholy and prescribed activities to snap them out of it or worse, to repent of sins presumed to cause it. But in many cases, John sensed not depression but a pruning away of attachments to things less than God. In those cases, John saw not disease or evil but an advance in spiritual maturity that called for validation and support from directors.

He called it, “The Dark Night of the Soul,” and his writings on it became classic texts of Christian spiritual literature.[1] John believed that attachments to possessions, positions, pleasures, and even to ideas of God and right belief get in the way of an open, receptive relationship to the real God beyond understanding and imagining. Loss of pleasure or consolation might mean not depression, but a spiritual pruning of attachments to free them for single-minded love of God.

Thus, devotees of John to this day insist upon the distinction between the dark night and depression. But I wish to suggest that while we must remember that the presence of one does not entail the presence of the other, neither should we rule out that a person can experience both simultaneously.

One can walk through the dark night without depression, and one can sink into depression without the dark night. But in that latter state, one can offer one’s depression to God as an occasion for detachment from ego ideals and enslaving possessions and claims. Since depression usually involves grief over lost attachments, one can pray for God to convert depression into a dark night.

John’s dark night offers encouragement to people who feel adrift in a desert of spiritual dryness. God dwells not too far away to perceive but too close: God abides within them, shaping, reforming, and purifying their hearts for unadulterated love and eventual joy. But to depressed people of faith, it offers an additional encouragement. They can choose to offer the depression to God for that same work, to allow God to convert despair to freedom.

You remember Kris Kristofferson’s lyric: “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.” Freedom comes with giving it all up to God, freedom to love God, yourself, and others again, nonpossessively and joyfully. That’s what so many experience on the other side of depression, myself included. I can’t help thinking that God often does the forming, freeing work then that God does in dark nights when we cannot see, when we can only trust.

[1] See Kieran Kavanaugh, OCD, and Otilio Rodriguez, OCD, trs., The Collected Works of St. John of the Cross. (Washington, DC: ICS Publications, 1991). For a very accessible discussion of the dark night, including its relationship to depression, see psychiatrist and spiritual director, Gerald G. May, The Dark Night of the Soul: A Psychiatrist Explores the Connection Between Darkness and Spiritual Growth. (San Francisco, California: HarperSanFrancisco, 2004).

0 Comments