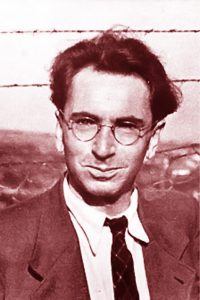

Viktor Frankl, Doctor of the Soul

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven (Matthew 5:10).

As neo-Nazis across the US prepare to descend upon Rome, Georgia later this week for an annual conference, let us reflect on the Holocaust.

If through the suffering and death of one Jew two millennia ago, God’s weakness overpowered the powerful and God’s foolishness outsmarted the wise (1 Corinthians 1:18-31), so through millions of Jews persecuted and martyred in the Holocaust, God did the same. The persecuting Nazis left no worthy legacy. Neo-Nazis swarm in pockets like hornets without a nest.

Today the Nazis only energize the desperately resentful. Yet, those whom they persecuted move us with their capacity to suffer and affirm life. Along with Anne Frank, Elie Wiesel, and other eloquent spokespersons for this spirit, Viktor Frankl speaks to me with special power and poignancy.

Frankl’s classic text, Man’s Search for Meaning, recounts with brutal candor his detention in concentration camps; yet, from his horror log, this psychiatrist developed a perspective on the human personality and therapy that still shapes the outlook and practice of thoughtful therapists. More fundamental than our motives for sex (Freud), power (Adler), or personal integration (Jung) is our search for meaning. Nobody finds their life’s meaning fully packaged before death, but the search for meaning animates the living.

He observed many who died suffering well, carrying dogged faith in life’s purpose through their last breath. Yet, he also observed those who gave up the quest and expired within a couple of days. Frankl himself persevered because he found even the slightest hopes worth living for.

He maintained hope of reuniting with his newlywed bride, whom he did not realize was killed shortly after Nazi guards separated them. He maintained hope that he would rewrite and publish a manuscript that the Nazis confiscated and destroyed. He later published it as The Doctor and the Soul. Moreover, he claimed to find meaning in suffering itself.

No one exercises greater freedom and courage than one who expectantly searches for meaning in suffering. Even in death camps, one could discover personal meaning in the concrete experience of daily life. From the suffering itself, good will emerge. The soul who lives by that faith is captive to no one, not even the Nazis.

At the end of a day when the Nazis deprived the detainees of even their survival rations of food, Frankl exhorted his comrades to continue the search for meaning. He recounted the conclusion of his address:

And finally I spoke of our sacrifice, which had meaning in every case. It was in the nature of this sacrifice that it should appear to be pointless in the normal world, the world of material success. But in reality our sacrifice did have meaning. Those of us who had any religious faith, I said frankly, could understand without difficulty. I told them of a comrade of who on his arrival in camp had tried to make a pact with Heaven that his suffering and death should save the human being he loved from a painful end. For this man, suffering and death were meaningful; his was a sacrifice of the deepest significance. He did not want to die for nothing. None of us wanted that.[1]

Let this courageous affirmation fill and form your spirit. Do not join those who circle the wagons in fear and resentment. Even amid suffering – or more precisely, especially amid suffering – there is too much loving to do for that.

[1] Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning. (New York: Washington Square Press, 1984), 104-105.

0 Comments