Hope and Prophecy

Grief is natural and necessary. A flesh wound heals with its inevitable pain, bleeding, scabbing, and scarring. It is neither pretty nor comfortable before the wound disappears or we adapt to it. Just so with grief’s angry protests and tearful sadness, its searching in the night, its overwhelmed anxiety that denies the loss one day and bargains with fate the next.

It is all part of a healing process, and if we need bleeding to clean out our wounds, we need weeping and talking it out to cleanse our broken hearts. As we need peroxide and bandaids if not stitches for flesh, so we need to reconstruct broken stories by telling them. Sometimes the grief mutes us, and we need a psalm or song or a friend to give us the words we need until the shock passes.

The Hebrew prophets gave the grief-stricken people words. The popular notion of prophecy as future-telling, while not entirely wrong, misleads us. Prophets bring a word from God into the present predicament. We remember prophets for poetic words and dramatic demonstrations to awaken the people to impending crisis, so we remember those who got that future event right. But their words also provide a frame for seeing God in godforsaken circumstances and ultimately finding the way back to hope from grief.

Exile: Hope Dashed

Hope, so fragile, shatters with devastating loss. With the death of a spouse, beloved parent, or child, with the crashing and burning of a career or business in which one has dedicated almost every resource, with divorce and estrangement from family, friends, and church, with marginalization or imprisonment due to misunderstanding or discrimination, with poverty and homelessness due to insufficient resources to pay for medical care, the possibilities of hope-destroying loss always hang over us. Such losses destroy hope because we built our dreams on the relationships and resources now lost. We cannot bear life without a dream.

God promised to David centuries before that an endless line of kings would follow him, and that God would guard and guarantee Israel’s survival and flourishing as long as they are faithful to God. So the people shared a dream confirmed by their kings, priests, and prophets again and again that, despite the rise of greater military powers like Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, and Persia, God would protect them and make their Temple the world’s temple, their faith the priestly faith to which the world would turn in reverence, their Zion the ultimate destination that all would visit with joy and gratitude.

Then Babylon invaded Jerusalem with a holocaust of murder and rape, with looting valuables and destroying homes, with tearing down and burning the delight of their eyes, the Temple of God, then taking the best, brightest, and wealthiest into exile. Among those they took was priest and prophet, Ezekiel, who enacted the trauma and loss before the invasion. When his wife, the “delight of his eyes,” died some time earlier, he startled the people with refusal to grieve or participate in rites of mourning because he knew that someday Jerusalem would not have time to grieve or bury their dead. He packed what little they would be able to upon exile and walked the streets as an alien. So it would be in the devastating loss of defeat and exile.

Hope From Grief: The Resurrection of Bodies

Ezekiel framed the problem as God’s having absconded because the people abandoned God with their worship of idols and their failure to honor God by treating the poor of the land with mercy. They made Jerusalem and the Temple unfit for God’s habitation, so God was not there to protect them. But the book begins with an image of God on wheels who accompanied them after all in exile. There hope from grief emerges.

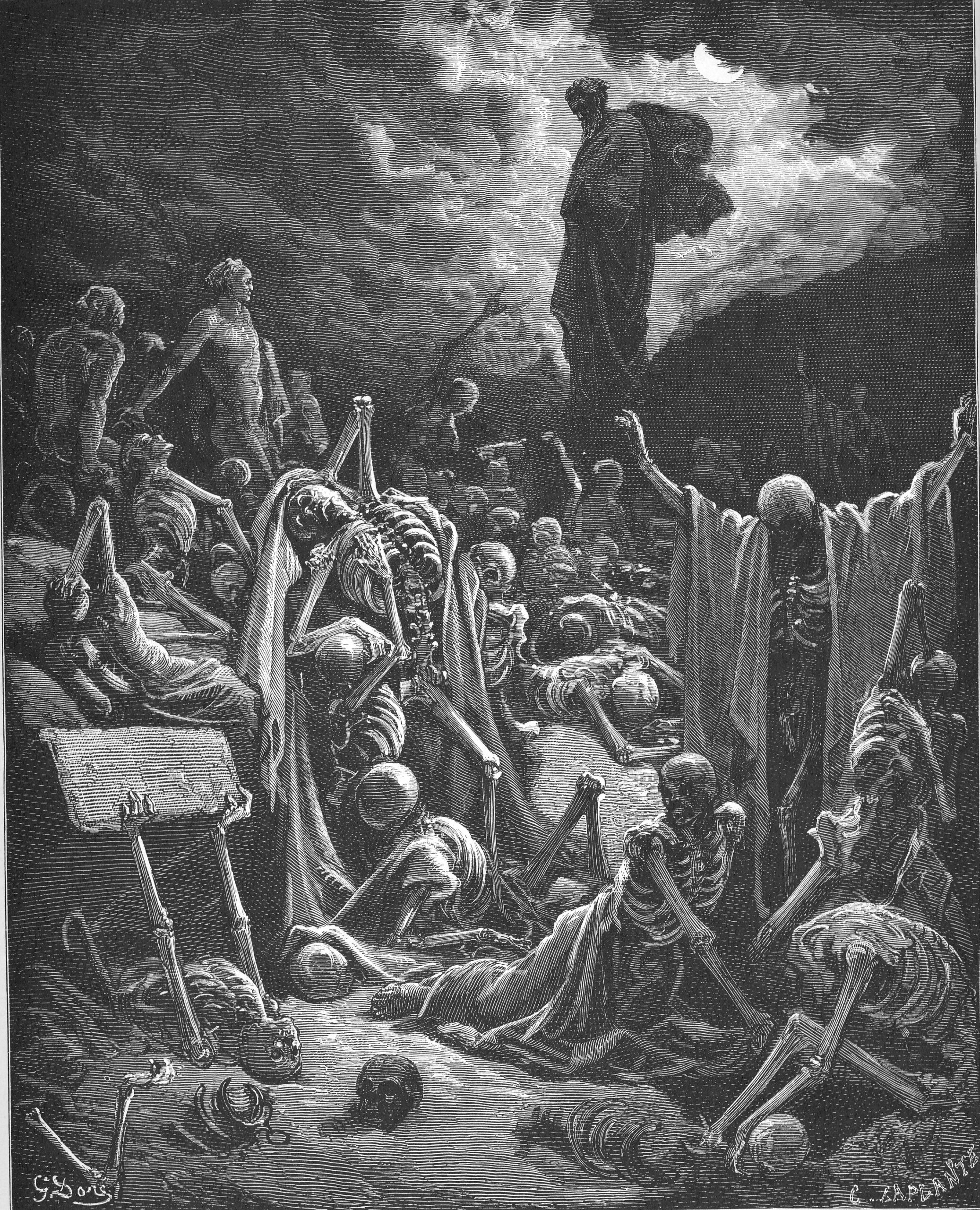

Hope reaches a dramatic climax in the apparently hopeless valley of dry bones. They represent exiled Judah, of course, utterly lifeless apart from God and their land, languishing and decaying. These bones lie exposed with no burial, no honor, abandoned in the arid heat with no pause for mourning. But God-on-wheels bids the prophet order their reconstruction and even call the breath, the spirit to enter them. After the rustling, cracking, and panting, they live with God and God with them, with hope restored.

Resurrection hope inherits this, from the resurrection of the body despite death to the restoration of relationship with God even amid apparent godforsakenness. We need not literally go into exile to appreciate Easter, but we need Good Friday, the recollection of the horror of Christ’s death and the square facing of the losses and threats to our hope. And for those in unconsolable silence, we must be Ezekiel, companioning them in their muteness, waiting for God with hope that defies hopelessness.

Related Posts

0 Comments