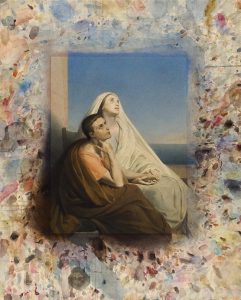

Good mourning will come for you as for Augustine and Monica.

Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted (Matthew 5:4).

Grief and mourning

All of us face significant losses. How we face them makes a great difference in how we manage psychologically and whether we thrive spiritually over the long haul.

Grief and mourning are the inner and outer aspects of a healing process. Grief stirs inwardly with the ache of yearning, sadness, anger, and feeling overwhelmed, lost, or numb. In mourning, we express those feelings outwardly to our fellows and to God.

Healing depends in large part on how we mourn. Bottling up grief can literally damage us physically and stultify our intimacy. On the other hand, overindulging our feelings and making bereavement our identity keeps joy at bay and can isolate us even more.

Augustine offers examples of good mourning and bad.

In his classic fifth century memoir, the Confessions — indeed the first autobiography in western literature — Augustine, Bishop of Hippo in North Africa, puts himself on the line page after page, sizing up his youthful immaturities and young adult vanities with brutal honesty and utmost humility. More deeply, he tells a story of God’s grace, of the Holy Spirit opening his heart, and he tells it in prayer to God.

Whether or not you ever read the Confessions, I want to share with you how he handled the theme of mourning, from bad mourning to good mourning.

For Augustine, good mourning not only leads us through the pain of loss to wisdom and resilience. It leads us closer to the alter of God, prepares us to receive God’s love. Reflect on your own history of grief and mourning as you consider the episodes below from the Confessions.

Good mourning? Or self-indulgence?

Late in Book One, Augustine admits to boyhood difficulties engaging in his studies, except when he read Virgil’s classic Aeneid. This epic poem offers the adventures of Aeneas, a Trojan whose exploits — including the Trojan horse — make him the ancestor of Rome. His romance with Dido, queen of Carthage, carried Augustine away emotionally. When abandoned by Aeneas, she commits suicide.

Augustine, the 43-year-old bishop writing the Confessions, regretted his youthful tears over romantic tragedy and others he indulged at theatres soon thereafter. He noted that, as a spectator to such drama, he safely had no skin in the game and pursued the experience to indulge sadness itself. Compassion is good, but not as a spectator sport, not as an indulgence with no challenge to take merciful action in real life.

Worse, he had no passion at all for God then, no yearning for God yet. So, his indulgence in such pathos over fictional characters in fleeting romances only exposed his confusion. Such melodrama did not make for good mourning.

Good mourning? Or loving too late?

In Book IV, he starts his career teaching rhetoric. The brash and cocky young Augustine scoffed at his mother’s Catholic Christianity. Newly engaged with the elitist Manichees, an eclectic sect that claimed to be more Christian than the Christians, he enjoys trashing Catholic Christianity to entertain his friends.

He holds one friend (whom he does not name) especially dear. When the friend falls gravely ill, his parents have him baptized. Remarkably, the friend suddenly recovers, and Augustine makes fun of the baptismal rite.

Until this time, his friend had been a listener, and Augustine the big talker. Previously, Augustine set the agenda for their time together, and the friend patiently went along. But his friend shocks Augustine with the force of his counterattack in defense of his baptism, telling Augustine that he will not repeat such talk if he wishes to remain his friend. Augustine backs off, and soon his friend’s illness returns, killing him.

“Black grief closed over me, and everywhere I looked I saw only death,” Augustine writes. “Everything I had shared with my friend turned into hideous anguish without him. My eyes sought him everywhere, but he was missing…. I had become a great enigma to myself, and I questioned my soul, demanding why it was sorrowful and why it so disquieted me, but it had no answer. If I bade it, ‘Trust in God,’ it rightly disobeyed me, for the man it held so dear was more real and more lovable than the fantasy in which it was bidden to trust. Weeping alone brought me solace and took my friend’s place as the only comfort of my soul.”[1]

These poignant words of mourning ring true. Yet, Augustine recognizes that he loved his friend too late. Having dominated their interactions, he received his friend’s love but had given too little before he died. Only at the last moment did he awaken to his friend’s energy and integrity, but there was no time left to honor it. So Augustine escaped into indulging the sadness as he had for the fictional Dido, rather than staying with the memory of friend he misses — or misses out on.

Good mourning? Or loving too late again?

Augustine suffers other failures to mourn along the way. Ambitious young men in that time and place often took common law wives from lower classes, only to drop them eventually to “marry up.”

So he has a common law wife of 15 years, and a son by their union. In Book VI, his mother catches up to him and persuades him to accept an arranged marriage to a young woman in a higher social position. This requires a delay for the prospective bride to reach the age of maturity. But he goes ahead and dismisses his common law wife, who returns home vowing never to marry another.

Grief seems to blindside him. He mourns,

“So deeply was she engrafted in my heart that it was left torn and wounded and trailing blood.”[2] She seemed “torn from my side,” and one gets the sense that he finally realized how much he loved her. But he concealed his mourning to keep appearances.

Good mourning at last

Despite his plans, Augustine never marries after that. He moves toward his famous conversion that, for him, entailed detachment from sexual needs. Ironically, his aforementioned mother, Monica, who wants to see him make it in the world, can forsake that dream for one higher aspiration: That he convert to Christianity and devote his life to the service of Christ.

His movement in that direction is the great drama of the Confessions. His mother’s unwavering love and encouragement of his faith play a supporting role. Finally, he does not love too late as he did with his friend and common law wife. Realizing and reciprocating his mother’s love, helps set the stage for his conversion.

Soon after his baptism, the autobiographical books of the Confession close in book IX with his mother’s death. But just before she falls ill and dies rather quickly, they enjoy an intimate, prayerful conversation. Both repent of their worldly ambitions and mutually experience union with God, with “That Which Is.”

After her unexpected but peaceful death two weeks later, Augustine mourns again in prayer:

“Little by little, I recovered my earlier thoughts about your handmaid, remembering how devout had been her attitude toward you, and how full of holy kindness, how willing to make allowances, she had been in our regard; and now that I was bereft of this, I found comfort in weeping before you about her and for her, about myself and for myself. The tears that I had been holding back I now released to flow as plentifully as they would, and strewed them as a bed beneath my heart. There it could rest because there were your ears only, not the ears of anyone who would judge my weeping by the norms of his own pride.”[3]

Good mourning: Lessons for our confessions

So, what do we learn from Augustine about good mourning? The lesson is very simple. Love now. Do not delay. Love the real people God places in your midst as they are, not just fantasies to satisfy your wishes. Listen to them, hear their voices, and when that calls for compassion, respond with acts of mercy and kindness.

Listen to your heart. Do not let frivolities like social status dictate your loyalties. As you listen to your heart and to those who love you, listen for the love of God that beckons through, calling you to live your truth in loving them. Then when death comes, your grief will be sharing in the suffering of Christ who first loved us, and your mourning will be a song of praise.

In a word, tomorrow’s mourning is only as good as today’s love.

Related Posts

Confessions of Augustine: A Gift from a Friend

Cleansing for Life with Augustine and Me

Endnotes

[1] Augustine, The Confessions, tr. Maria Boulding. (New York: New City Press, 1997), 62-63.

[2] Ibid. 113.

[3] Ibid. 178.

Image: Ary Scheffer, Saint Augustine and Saint Monica, 1845, Public Domain.

0 Comments