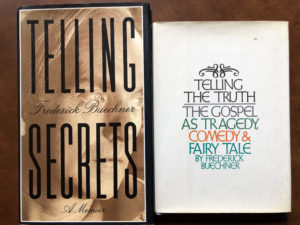

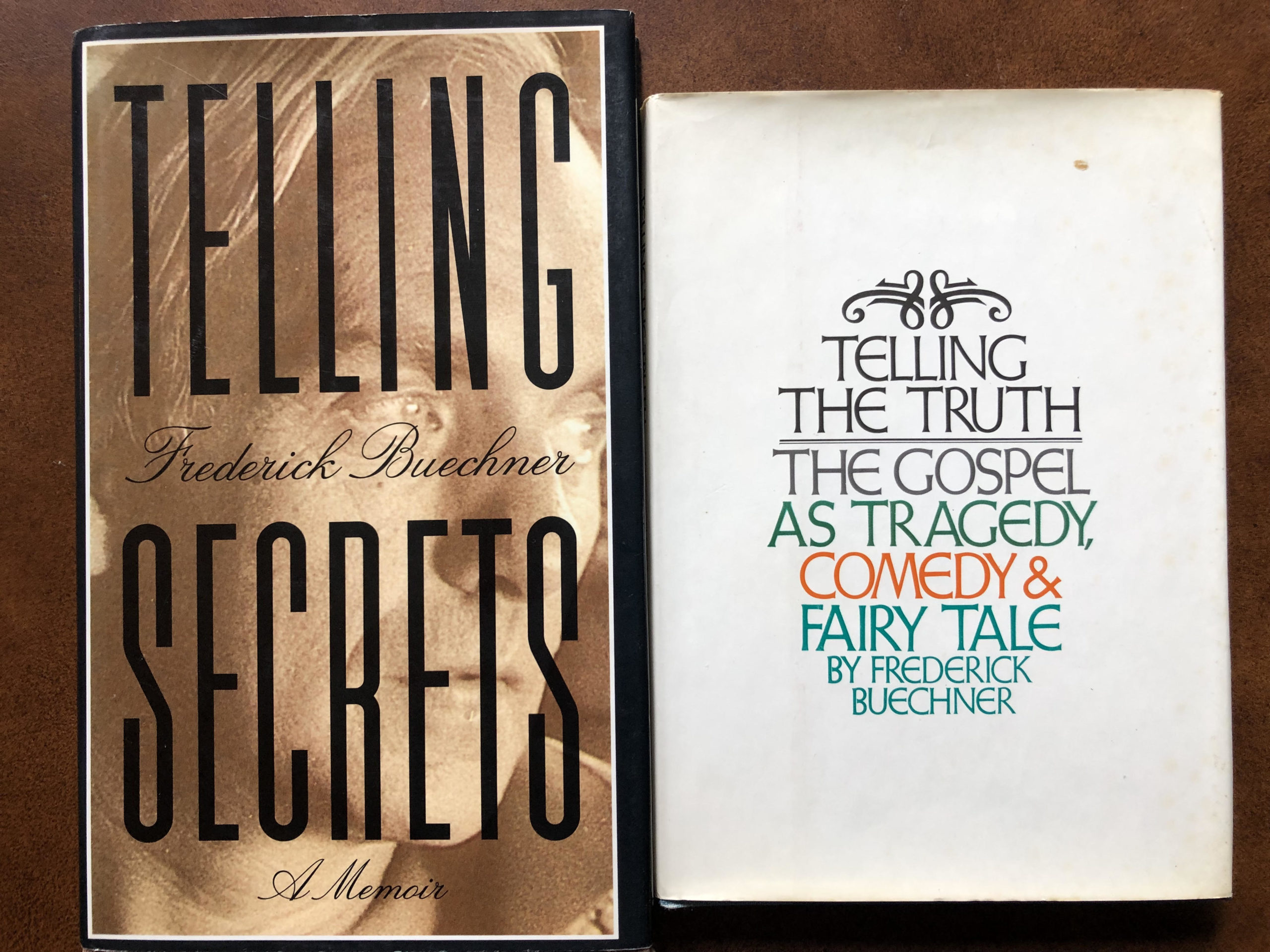

Two Books On Telling By Frederick Buechner

Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted (Matthew 5:4)

Telling and Healing

The first Beatitude blesses the poor in spirit who give thanks like beggars for receiving all they need from God (Matthew 5:3). In a sense, it blesses those who face reality under a gracious God. By blessing those who mourn, the second Beatitude, too, blesses those who face reality, only now, the darker side. They face the normal tragedy of life punctuated with loss.

We observe grief at funerals, but losses recur all along life’s way. Loss of functions and faculties as we age, loss of self-esteem and hope as we suffer setbacks, loss of jobs, money, relationships: Seldom does a page turn in any life story without accounts of such losses. Even gains like marriage, a new job, moving to the dream house, and so on incur opportunity costs, the things we leave behind so we can move forward.

So Jesus’ blessing of those who mourn touches all people who face and name the tragedies of loss in their lives. Healing requires telling to release the secrets that haunt and to speak the truth that frees. Frederick Buechner wrote two books on telling that can help those who mourn receive the comfort that comes by grace.

Telling the Truth: The Gospel As Tragedy, Comedy, and Fairy Tale

In the first of his two books on telling, Telling the Truth: The Gospel As Tragedy, Comedy, and Fairy Tale, Frederick Buechner offers a writer’s wisdom for preachers on how to tell the Gospel as God’s story lives out in our lives. He counsels preachers to attend to the tragedy in people’s lives first. Otherwise, the irony and hope of the Gospel has nowhere to land in the hearer’s heart.

Beneath our clothes, our reputations, our pretensions, beneath our religion or lack of it, we are all vulnerable both to the storm without and to the storm within, and if ever we are to find true shelter, it is with the recognition of our tragic nakedness and need for true shelter that we must start. Thus it seems to me that this is also where anyone who preaches the Gospel has to start too – after the silence that is truth comes the news that is bad before it is good, the word that is tragedy before it is comedy because it strips us bare in order to ultimately clothe us.

This is, of course, where Jesus starts, and his word of tragedy is “Come unto me all ye who labor and are heavy laden”….When he says, “Take up your cross and follow me,” I think that he is saying the same thing because before it means take up some special mission or some special sacrifice or responsibility, “take up your cross,” means simply take up the burden of your own life because for the time being anyway, maybe that is burden enough. Take it up in the sense of touch it and taste it and listen to it, look at yourself and your own life and smell the smell of your mortality and nakedness. All of you. Who are the poor naked wretches? Who are the ones that labor and are heavy laden? All ye, Jesus says – that is his tragic word to us, and his preachers must speak it after him if they are to be true to his truth (Telling the Truth, pp.33-34).

Comfort comes in knowing that our pain does not separate us from the human race as it may seem. Rather, our pain points to our common plight with every one who shares with us “tragic nakedness and a need for true shelter.”

Mourning prepares us to hear the good news in Jesus’ words that invite, welcome, call, and teach the way to ourselves and beyond ourselves to the God in whose image we were made. Moreover, it draws us into the life of Christ, who suffered with and for us and who makes himself known to us as our suffering becomes part of his (see Philippians 3:10-11).

Telling Secrets: A Memoir

Therefore, Buechner models for us a critical task of mourning that is also a critical task of spiritual growth: Telling our stories. As the theological world became more aware of the centrality of narrative, Buechner led by telling his story in memoirs including The Sacred Journey, Now and Then, Telling Secrets, The Longing for Home, and The Eyes of the Heart.

Especially in the second of his two books on telling, Telling Secrets: A Memoir, he hones in on his grief over his father’s suicide when he was a boy, his daughter’s anorexia, and the whole journey of love and loss in his family story. In Telling Secrets, he explains:

This is all part of a story about what it has been like for the last ten years or so to be me, and before anybody else has the chance to ask it, I will ask it myself: Who cares?…

But I talk about my life anyway because if, on the one hand, hardly anything could be less important, on the other hand, hardly anything can be more important. My story is important not because it is mine, God knows, but because if I tell it anything like right, the chances are you will recognize in many ways that it is yours. Maybe nothing is more important than that we keep track, you and I, of these stories of who we are and where we have come from and the people we have met along the way because it is precisely in these stories in all their particularity…that God makes himself known to each of us most powerfully and personally. If this is true, it means that to lose track of our stories is to be profoundly impoverished not only humanly but also spiritually (Telling Secrets, pp.29-30).

With his own life, Buechner demonstrates the power of telling our stories in working through grief and becoming stronger at the broken places. Loss shatters our narratives. Telling our stories helps us put them back together and more, helps us discover the grace woven in them and emerging from them like a resurrection.

Through the power that memory gives us of thinking, feeling, imagining our way back through time we can at long last finally finish with the past in the sense of removing its power to hurt us and other people and to stunt our growth as human beings.

The sad things that happened long ago will always remain part of who we are just as the glad and gracious things will too, but instead of being a burden of guilt, recrimination, and regret that make us constantly stumble as we go, even the saddest things can become, once we have made peace with them, a source of wisdom and strength for the journey that still lies ahead. It is through memory that we are able to reclaim much of our lives that we have long since written off by finding that in everything that has happened to us over the years, God was offering us possibilities of new life and healing which, though we may have missed them at the time, we can still choose and be brought back to life by and healed by all these years later. (Telling Secrets, pp.32-33).

In his two books on telling, Telling the Truth and Telling Secrets, Frederick Buechner helps us understand Jesus’ audacious promise of comfort for those who mourn. Grief opens our eyes and ears to Christ’s good news that he promised in the first place to the poor, the captive, the blind, and the oppressed (see Luke 4:18-19). And as we tell our stories, we restore them after loss, and more, we find our story told in God’s story and God’s story in ours.

Related Posts

For a succinct collection of some of Buechner’s essays on grief from several of his works, see A Crazy, Holy Grace.

Reading this post resonated with me deeply as it dovetailed personal conversations about my grief from yesterday. Opening yourself up to others to share your grief expands your heart’s understanding of the commonalities that bind us all together.

Thank you, Cheryl. Very well said!